Note to myself: In addition to today’s outstanding resource, please review again

- “AMAX4 Lecture – COMPLETE” For The Treatment Of Life-Threatening Anaphylaxis And Asthma

Posted on February 19, 2024 by Tom Wade MD - “AMAX4 Simulation MASTER”: A Real-Time Simulation Of A Severe Anaphylaxis/Asthma Treatment

Posted on February 20, 2024 by Tom Wade MD

Today I link to, embed, and excerpt from The Curbsiders‘ “#111: Why Can’t Your Patient Breathe? An Exam-Driven Approach to Pediatric Respiratory Failure“.* June 5, 2024 | By Sam Masur.

*Ward B, Powell W, Wyatt M, Chiu C, Berk J, Masur S. “#111: Why Can’t Your Patient Breathe? An Exam-Driven Approach to Pediatric Respiratory Failure”. The Cribsiders Pediatric Podcast. https:/www.thecribsiders.com/ June 5, 2024.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Summary:

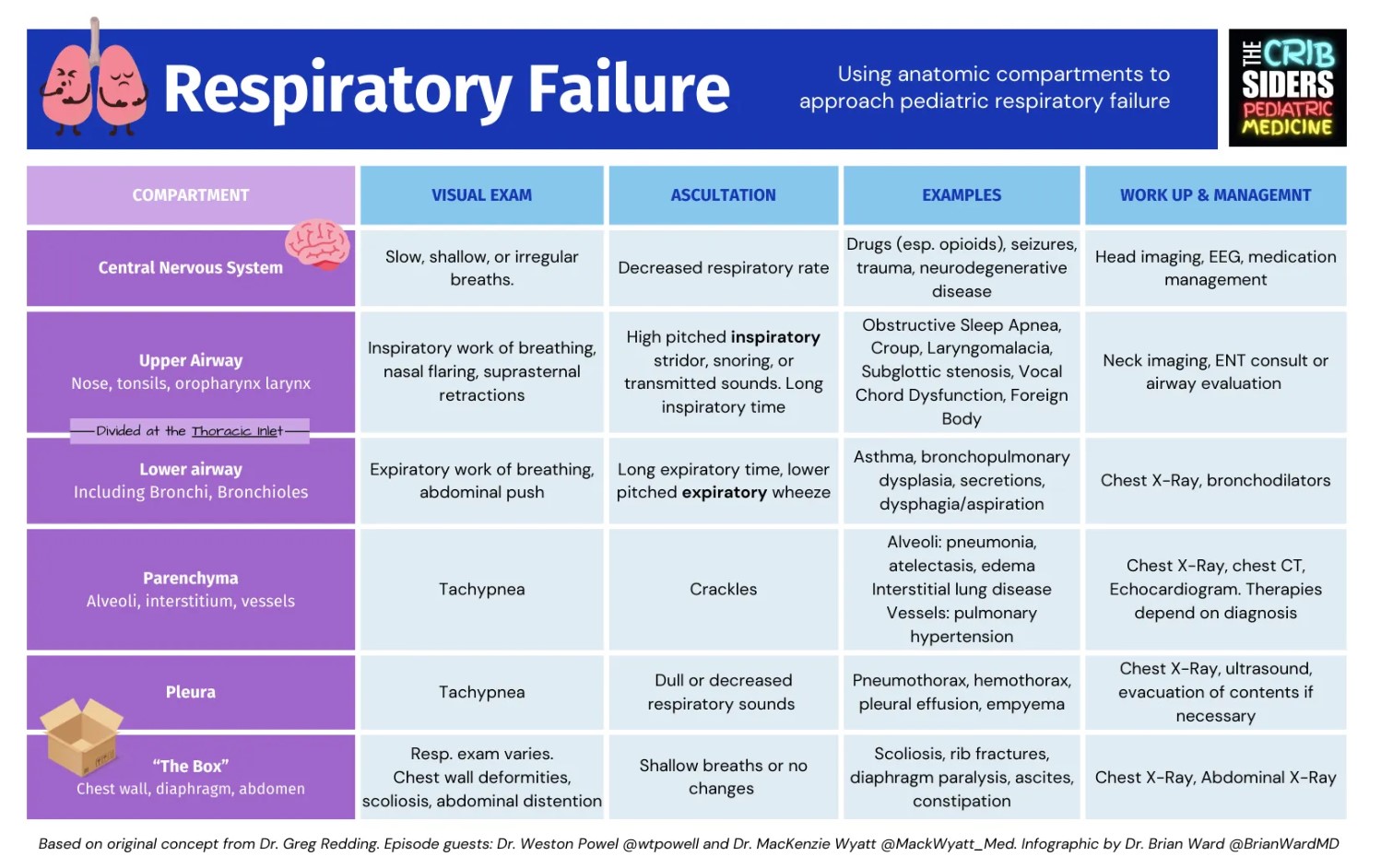

Respiratory failure is one of the scariest presentations in the clinic, ED, and hospital. How do you generate a differential and plan for the child who cannot breath? Pulmonologists Dr. Powell and Dr. Wyatt describe how we can use our physical exam and an anatomic approach as a framework for diagnosis and initial management of respiratory failure in children. Next time you find yourself staring at the pulse ox reading 85% and hoping for it to change, take a peek at this schema.

Respiratory Failure Pearls

- The first step when called to the bedside for a patient in respiratory distress is to take a deep breath yourself.

- A diagnostic approach can reduce anchoring bias, especially in patients with multiple overlapping processes.

- Inspiratory noises are more associated with upper airway processes whereas expiratory sounds are more associated with lower airway issues.

- The physical exam is a great tool. Use it!

Respiratory Failure Notes

Drs. Powell and Wyatt describe how we can use the compartments of breathing as a framework for diagnosis and initial management of respiratory failure in children. This is a framework described by their mentor, Dr. Gregory Redding, at Seattle Children’s Hospital. But before we get into the specifics, let’s talk about schemas real quick:

Schemas and Frameworks in Clinical Reasoning:

Frameworks, schemas, or models help us use our problem representations to come up with differential diagnoses and direct our thinking (Cammarata and Dhaliwal, 2023). Standard approaches to problems can be a helpful teaching tool for trainees and learners.

The Compartments Model is an anatomic approach to pediatric respiratory failure that emphasizes the clinical exam, both work of breathing and auscultation. It is not mutually exclusive with other ways to describe or categorize respiratory failure such as hypoxemic vs hypercarbic respiratory failure or restrictive vs. obstructive pathologies.

The six compartments are:

- Central nervous system

- Upper Airway

- Lower Airway

- Parenchyma

- Pleura

- “The Box” or the structures surrounding the lungs

Central Nervous System

The Concept: The brain and brainstem and spinal cord control breathing and send signals through C3, 4, and 5 (keep the diaphragm alive, remember that one?). Respiratory failure due to CNS issues will typically present as decreased respiratory drive.

Physical Exam (PE): The lungs will sound the same, but the rate will be decreased or absent.

Examples: Medications and intoxications (especially opioids, benzos, and anti-seizure medications), head trauma, severe metabolic derangements

Upper Airway

The Concept: The upper airway includes the nose, mouth, pharynx and larynx above the thoracic inlet. Problems here are generally obstructive in nature and present with a long inspiratory time.

PE: Inspiratory work of breathing, nasal flaring, suprasternal retractions with high-pitched inspiratory stridor, snoring, or transmitted sounds on auscultation.

- Pro tip: Puting the stethoscope to the mouth can help the clinician identify referred upper airway noises.

Examples: Croup, nasal congestion, craniofacial anomalies like choanal atresia or macroglossia/micrognathia, obstructive sleep apnea, subglottic stenosis, vocal cord dysfunction, foreign body (depending on where it is).

Lower Airway

The Concept: The lower airway includes the bronchi and bronchioles. In other words, every airway from just below the thoracic inlet to just above the respiratory bronchioles and alveolus.

PE: Expiratory work of breathing, abdominal push. On auscultation, long expiratory time, lower pitched expiratory wheeze

Examples: Asthma, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, secretions, dysphagia/aspiration, small foreign body that made its way down.

Why the thoracic inlet? The upper and lower airway experience different pressure dynamics. Recall that on inspiration, negative pressure is generated in the thorax; the diaphragm moves down and the chest wall moves out, creating a relative vacuum. Under normal conditions, this negative pressure is transmitted up through the airways into the trachea and pulls air in from the atmosphere. This negative pressure provides a collapsing force to the airways outside the thorax, however inside the thorax, the negative pressure provides outward force and splitting that keeps the airways open. The opposite is true on expiration: lung recoil and expiratory effort offer inward/closing force on the airways inside the thorax. Outside the thorax, that same pressure pushes air out and pushing the airways open.

Parenchyma (“the Meat”)

The Concept: The “meat” of the lung includes the alveoli, interstitium, and vessel. These are all involved in gas exchange. Pathophysiology here is more variable and can be further broken down into the different sub-compartments.

PE: Tachypnea is often present. On auscultation, crackles can be heard, however this can vary.

Examples:

- Alveoli: pneumonitis, atelectasis, edema, pneumonia

- Intersitium: Interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis

- Vessels: pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary hemorrhage

Pleura

The Concept: Changes in the pleura, or the lubricated double-membrane and potential space between the lungs and the chest wall, can cause respiratory failure by reducing distensibility of the lung parenchyma. Most often, this is caused by things being in that space that ought not be there.

PE: Reduced transmission of lung sounds, usually focally. Pain can cause splinting, tachypnea, and shallow breaths.

Examples: pneumothorax, hemothorax, pleural effusion, fibrosis of the pleura

“The Box”

The Concept: Everything that surrounds the chest, like the ribcage and chest wall, the spine, and the abdomen can reduce the space that the lung gets to use for gas exchange.

PE: Abnormal chest wall, back curvature, or distended abdomen

Examples: Abdominal competition (constipation, ascites, profound obesity), severe scoliosis, congenital rib abnormalities, rib fractures.

Multi-Compartment Respiratory Failure

Oftentimes, patients will have multiple pathologies occuring at once or overlapping processes contributing to their illness. This schema is especially useful in complex presentations and can give clinicians tangible steps in otherwise sticky clinical situations.

Links

Lastly, as mentioned in the episode intro, here is “Curiosity”, an article by Dr. Faith Fitzgerald.