Additional Resources

- Access the interactive tool here

- Read the Guideline At-a-Glance here

- Visit the guideline hub here

Today, I review excerpts from Section 4 Treatment from ACC 2023 Chronic Choronary Disease Guideline.

2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Circulation. 2023 Aug 29;148(9):e9-e119. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168. Epub 2023 Jul 20.

All that follows is from the above resource.

4 Treatment

4.1 General Approach to Treatment Decisions

Recommendations for General Approach to Treatment Decisions

Referenced studies that support the recommendations are summarized in the Online Data Supplement.

COR LOE Recommendations 1 C-LD

1. In patients with CCD, clinical follow-up at least annually is recommended to assess for symptoms,1-12 change in functional status, adherence to and adequacy of lifestyle and medical interventions,13-15 and monitoring for complications of CCD and its treatments.16-18

2b B-NR

2. In patients with CCD, use of a validated CCD-specific patient-reported health status measure may be reasonable to assess symptoms, functional status, and QOL.19-23

Synopsis

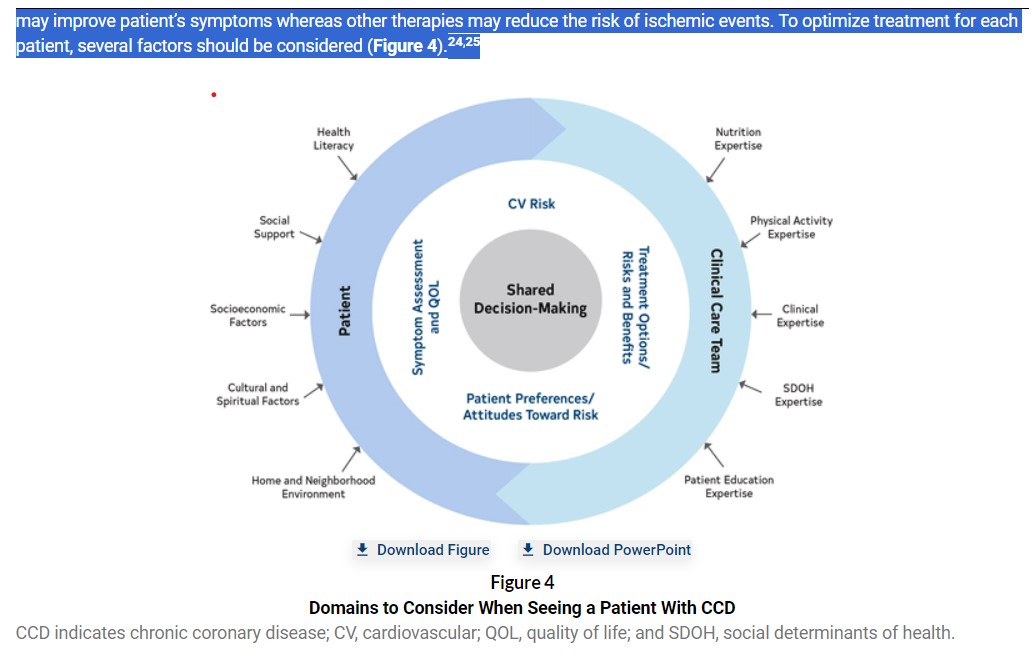

The ultimate goals for treatment of CCD are to prolong survival and improve QOL. To do this, treatments should target a reduction in (1) cardiac death, (2) nonfatal ischemic events, (3) progression of atherosclerosis, and (4) symptoms and functional limitations of CCD while considering patient preferences, potential complications of procedures/medications, and costs to the health care system. When engaging patients in shared decision-making (Section 4.1.3), clinicians should clearly identify that some therapies may improve patient’s symptoms whereas other therapies may reduce the risk of ischemic events. To optimize treatment for each patient, several factors should be considered (Figure 4).24,25

First, a global assessment of the risk of the patient is needed (Section 3), including both the risk of ischemic events and complications of potential treatment options. Second, obtaining a careful assessment of symptoms of CCD, functional limitations, and QOL is important. Third, SDOH (Section 4.1.4) must be considered. Fourth, the patient must be educated (Section 4.1.2) so they can actively participate in shared decision-making (Section 4.1.3). Finally, a team-based approach (Section 4.1.1) can help patients and clinicians navigate this process.

Recommendation-Specific Supportive Text

1. Patients with CCD comprise a heterogeneous group that includes those with or without angina, a history of coronary revascularization, and previous ACS. The goals of routine clinical follow-up in these patients include: (a) to assess for new or worsened symptoms, change in functional status, or decline in QOL; (b) to assess for adherence to and adequacy of recommended lifestyle and medical interventions, including physical activity, nutrition, weight management, stress reduction, smoking cessation, immunization status, blood pressure (BP) and glycemic control, and antianginal, antithrombotic, and lipid-lowering therapies13-15; and (c) to monitor for complications of disease or adverse effects related to therapy.16,17 Although there are insufficient data on which to base a definitive recommendation regarding frequency, clinical follow-up evaluation at least annually is recommended and may be sufficient if the patient is stable on optimized GDMT and reliable enough to seek care with a change in symptoms or functional capacity. For select individuals, an annual in-person evaluation may be supplemented with telehealth visits when clinically appropriate.26 Implementation of remote, algorithmically driven-disease management programs may provide a useful adjunctive strategy to achieve GDMT optimization in eligible patients.27

2. Revascularization1-3,12 and antianginal medications4-7 primarily reduce the symptoms of CCD. The factor most strongly associated with improvement in symptoms and QOL after revascularization is the burden of ischemic symptoms before intervention.8-12,28-30 Thus, assessment of symptoms at each clinic visit is important to identify times when additional interventions could be useful, as well as to quantify the symptomatic response to interventions. Observational studies suggest that clinicians may inaccurately estimate the burden of ischemic symptoms,19-21 which can lead to under-22 or overtreatment.21 Validated patient-reported disease-specific health status measures (eg, 7-item Seattle Angina Questionnaire31)* may help to reliably quantify the burden of CCD symptoms and reduce variation in assessment among clinicians.23 Furthermore, patient-reported disease-specific health status instruments also measure how the patient’s angina affects their QOL, which should be an important component of the treatment decision process. Although several studies showed deficiencies with clinician estimation of patient’s symptoms, no studies show an improvement in quality of care or outcomes with routine use of patient-reported measures in clinical care.

———————————————————————————————–

Resources For The Seattle Angina Questionnaire

- The Seattle Angina Questionnaire

- Development and Validation of a Short Version of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire

- State of the Art Review: Interpreting the Seattle Angina Questionnaire as an Outcome in Clinical Trials and in Clinical Care [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 May 1; 6(5): 593–599. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7478. Merrill Thomas 1, Philip G Jones 1, Suzanne V Arnold 1, John A Spertus 1.

——————————————————————————————————––

Resuming Excerpts From Section 4

4.1.1 Team-Based Approach

Recommendation for Team-Based Approach

Referenced studies that support the recommendation are summarized in the Online Data Supplement.

COR LOE Recommendation 1 A

1. In patients with CCD, a multidisciplinary team-based approach is recommended to improve health outcomes, facilitate modification of ASCVD risk factors, and improve health service utilization.∗ 1-13

Synopsis

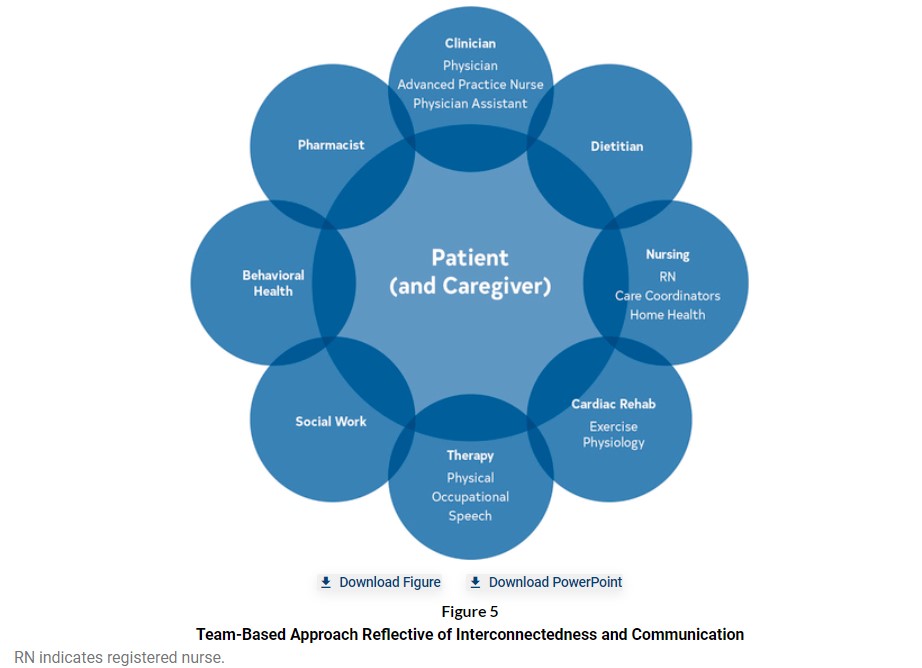

A patient-centered, team-based approach that focuses on shared decision-making is essential to monitoring and managing patients’ CCD symptoms throughout their disease course. These recommendations apply to all aspects of clinical practice for long-term management of CCD. A team-based approach can effectively be applied to nearly all aspects of CCD management and care. Continuous communication among the care team, the patient, and any caregivers is essential to optimize outcomes and meet patient needs. Figure 5 reflects the interconnectedness of the patient and caregiver to the care team and the care team members to each other. Components of the health care team include but are not limited to: physicians; nurse practitioners; physician assistants; nurses and nursing assistants; pharmacists; dietitians; exercise physiologists; physical, occupational, and speech therapists; psychologists; and social workers.

Recommendation-Specific Supportive Text

1. RCTs and systematic reviews with meta-analysis show that a patient-centered, multidisciplinary, team-based approach can improve patient self-efficacy, health-related QOL, and ASCVD risk factor management compared with usual care in patients with CCD who also may have hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia.1-8,11-13,15-34 Patients actively involved in their care with the medical team tend to have greater knowledge and confidence in self-management, which improves health-related QOL.1,21,32 Team-based care also facilitates behavior change and promotes weight loss, tobacco cessation, and reduces depression.8,12,16,31,33,35 A team-based approach may be more cost-effective and cost-efficient compared with usual care and reduces emergency department visits, unplanned health service utilization, cardiovascular complications in patients with diabetes, and readmission costs.6,7,9,10,20-22,27,28,31,32,34 A large cohort study comparing health care resource utilization of >1 million patients with either diabetes or ASCVD found that, overall, health care resource utilization was comparable among patients receiving care from physicians compared with advanced practice providers, although physicians work with larger patient panels.9 Communication through telehealth, patient education sessions, specialty clinics, medication therapy management, and patient decision support aids are appropriate and useful methods for providing patient care.36 Refer to Sections 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, and 7 for management.

4.1.2 Patient Education

Recommendations for Patient Education

Referenced studies that support the recommendations are summarized in Online Data Supplement.

COR LOE Recommendations 1 C-LD

1. Patients with CCD should receive ongoing individualized education on symptom management, lifestyle changes, and SDOH risk factors to improve knowledge and facilitate behavior change.1

1 C-LD

2. Patients with CCD should receive ongoing individualized education on medication adherence to improve knowledge and facilitate behavior change.2-4

Synopsis

Patient education is defined as “the process by which health professionals and others impart information to patients that will alter their health behaviors or improve their health status.’’1,5 Systematic reviews of studies using educational interventions suggest they improve patient knowledge and facilitate behavior change,1 although impact on sustained lifestyle change, cholesterol and BP levels, and morbidity and mortality rates are less clear.5-7 A meta-analysis of secondary prevention programs suggested education and counseling after MI reduced mortality but not recurrent MI.6 In contrast, a review of RCTs on educational interventions among patients with various manifestations of coronary disease concluded that education had no effect on total mortality, recurrent MI, or hospitalizations.5 Yet, Swedish registry data suggest that the education component of CR is strongly linked to cardiovascular and total mortality.7 Published studies of educational interventions for patients with CCD, whether provided in person or by Internet, are heterogeneous, often incompletely described, many are short-term, and outcomes assessment varies. At this time, there are insufficient comparative data to provide clinicians and their care teams assistance when choosing among interventions, a gap that should be addressed in future research studies.

4.1.3 Shared Decision-Making

Recommendations for Shared Decision-Making

Referenced studies that support the recommendations are summarized in the Online Data Supplement.

COR LOE Recommendations 1 C-LD

1. Patients with CCD and their clinicians should engage in shared decision-making particularly when evidence is unclear on the optimal diagnostic or treatment strategy, or when a significant risk or benefit tradeoff exists.1-3

2b B-R

2. For patients with CCD and angina on GDMT who are engaged in shared decision-making regarding revascularization, a validated decision aid may be considered to improve patient understanding and knowledge about treatment options.4

Synopsis

Shared decision-making is a collaborative decision-making process that includes patient education about risks, benefits, alternatives to treatment and testing options, and clinician ascertainment of patient values and goals. Shared decision-making helps to maximize patient engagement in medical decision-making, increase patient knowledge about their care, and align treatment decisions with patient preferences. Even when evidence suggests one treatment or testing modality compared with another may lead to improved cardiovascular outcomes at a population level, the optimal treatment or testing choice for an individual patient may vary based on patient values and preferences, as well as the financial implications of the choice to the patient. Decision aids can improve knowledge and reduce decisional conflict in shared decision-making, but few validated decision aids are available for patients with CCD. Clinician-patient conversations, as well as corresponding educational materials, should be tailored to the patient’s preferred language, reading level, health literacy, and visual acuity.

4.1.4 Social Determinants of Health

Recommendation for SDOH

Referenced studies that support the recommendation are summarized in the Online Data Supplement.

COR LOE Recommendation 1 B-R

1. In patients with CCD, routine assessment by clinicians and the care team for SDOH is recommended to inform patient-centered treatment decisions and lifestyle change recommendations.∗ 1-8

fig10 when server ready

4.2.2 Mental Health Conditions

Recommendations for Mental Health Conditions

Referenced studies that support the recommendations are summarized in the Online Data Supplement.

COR LOE Recommendations 2a B-R

1. In patients with CCD, targeted discussions and screening for mental health is reasonable for clinicians to assess and to refer for additional mental health evaluation and management.1-4

2a B-R

2. In patients with CCD, treatment for mental health conditions with either pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic therapies, or both, is reasonable to improve cardiovascular outcomes.2,4-6

Synopsis

Mental health has a major role in overall cardiovascular health and well-being in patients with CCD.7 Mental health is defined as “a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.”8 Mental health can have positive or negative effects on cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes.7,9 It is estimated that 20% to 40% of patients with CCD have concomitant mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.10,11 Meta-analyses have shown that negative psychological states (eg, general distress) are associated with MACE in men and women with CCD.12 Despite being a modifiable prognostic risk factor for CCD outcomes, screening for mental health disorders is seldom addressed in the clinical setting.4,13 Potentially underpinning the bidirectional relationship between mental health and CCD is the resulting influence on health behaviors (eg, medication and CR adherence, diet, physical activity, sleep, smoking) and risk factors (eg, BP, lipids, body mass index [BMI], inflammation, thrombosis).4,7 Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic treatments may reduce recurrent cardiovascular events and mortality rate in patients with CCD.5,14-17 See Section 4.1.4 for discussion of the interplay between mental health and SDOH.

Table 6Suggested Screening Tool to Assess Psychological Distress: Patient Health Questionnaire-2 Depression Screen

Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? Not at all Several days More than half the days Nearly every day Little interest or pleasure in doing things 0 1 2 3 Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless 0 1 2 3 Total score of ≥3 warrants further assessment for depression.

Table 7Suggested Screening Questions to Assess Psychological Health

Well-being parameter Question Health-related optimism How do you think things will go with your health moving forward? Positive affect How often do you experience pleasure or happiness in your life? Gratitude Do you ever feel grateful about your health? Do you ever feel grateful about other things in your life?